Midnight Oil has always been about no compromise. From their very first album, they rewrote the rule book. On stage, they are pure power and passion.

Together with INXS and AC/DC, Midnight Oil are one of Australia’s greatest rock exports but unlike their contemporaries, they have managed to maintain their unique Australian heritage. Their lyrics speak of land rights and the environment. They are the rock and roll watchdogs of not only Australia, but the world. Midnight Oil have used their position to create awareness in a world gone wrong with fossil fuels and nuclear waste. Their protest concert outside the Exxon building in New York was reported globally.

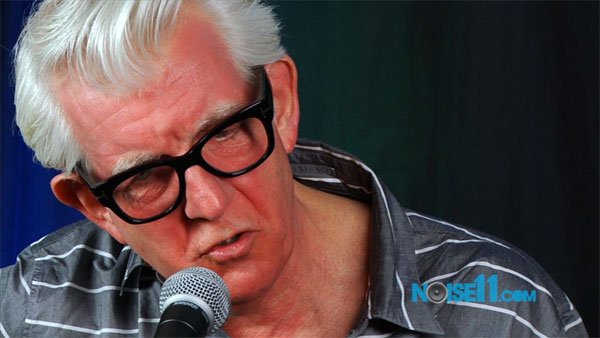

Outspoken lead singer Peter Garrett is often heard talking about political issues but is rarely heard talking about his music.

MIDNIGHT OIL REFORM FOR 2017 SHOWS

Paul Cashmere caught up with Garrett to discuss Midnight Oil, the band and their music.

PC: What issues are The Oils covering on Redneck Wonderland?

PG: Redneck Wonderland in some ways is just a particular reaction about bigotry, blindness, historical amnesia, conservative nasty right wing politics and, maybe, subliminally, it’s a reaction for The Oils to be yet doing another record in Australia about their place in their time. So yeah, it’s a squeal against the narrow minds.

PC: The last album Breathe broke the tradition of The Oils anger.

PG: We always saw Breathe literally as a breathing space record. It was going in a completely different direction to the way everybody was taking their music at the time. But working with someone like Malcolm Burn and working with a semi acoustic approach to it meant that when the songs came up in a natural way, we just put them down that way as well. It wasn’t a record that was laboured over at all. It wasn’t meant to be a big hit you over the head type of record. It was meant to be much more subtle and organic than that. But I think when you’ve been working together for so long like we have, you’ve either got that thing about picking up on what someone else is doing or you haven’t. And when everybody picks up on something together, then maybe there’s a track there.

PC: Why did it take you 20 years to put out a greatest hits album?

PG: I think it’s something that you’ve gotta be in the right frame of mind for or you’re not going to be excited about it at all. Or you are just going to see it as one of those necessary evils of the business. But I think there was that brief window of opportunity there for about 10 minutes when we all got excited and tried to image what it would be like if sat in a room, turned off the lights and had The Oils walk in and play for you. In a sense, it was an ideal gig for us, but also the opportunity to go back through some of the old tapes and bake then up and squeeze some extra life out of them. Then when we listened back we were all kind of pleasantly surprised. We thought “ah, this works”, you know. And we chose all the orders ourselves and through some other bits and pieces in to show everyone where we were going. It wasn’t too painful.

PC: Midnight Oil are one of the most dynamic live bands in the world. Why hasn’t a complete Oils show ever been captured as a live album?

PG: Well Scream In Blue was a record we did in 1992 or 1993 that had stuff from other places. We haven’t pulled one off one show. The closest we’ve come to it was a series of shows that we did at the Capital Theatre in Sydney years and years ago, which were filmed by a film maker named David Bradbury. We did get some very hot performances from that night. They are floating around on a bootleg somewhere. It’s probably better that they are bootlegs rather than albums that someone has to pay for.

PC: When you made your first album, it would have almost been impossible to visualise the ride you were about to start.

PG: I don’t think we’ve ever been particularly career minded. Certainly at that stage all we were thinking about was do we have enough money to get into town and make the record. I remember we took our advances and bought some lunch because we hadn’t eaten for a while. It was that sort of stuff which I think is probably typical for bands when they start out. And it was a record that when we made it, the guy who made it said “well I can only say one thing with confidence that this is never going to get played on radio and you guys are never going to be a success”. But I’ve enjoyed making the record because there was a lot of spirit in it”. And I think our attitude to that has always been the same. Any kind of prominence that we’ve achieved with albums or songs has always inevitably been a bi-product of us always trying to reach a certain point in the band with the music and what we were trying to say.

PC: The media were slow to discover The Oils, but the band seemed to have almost an instant live following?

PG: Well it’s a lucky combination of personalities and I think we just got into this bond with the audience. In many ways it was people that were keeping us alive by coming back, and back and back again. You can’t overstate that incredible rope that exists on the river were both band and audience are floating someways together. We don’t actually write to conform to people’s expectations of what we’ll produce as a band musically. We certainly perform to the expectation to the extent of wanting to give everything that we have. And I think we just had a very pure idea about the music, that it shouldn’t be defiled. It’s not an astonishing thing to say. I think over the centuries people have had strong views about what they are producing and their art and how they want to see it go out there. It seemed quiet natural to us. We just didn’t want to sell out you know.

PC: So what changed when you proceeded to your first round of success with Place Without A Postcard?

PG: Ah, paid off some debts. Found that the audience was coming in increasing numbers, so we just played to more people. And I think it probably just increases people’s confidence as a band when they discover people are starting to come onto them. We realised that the audience was opening up. I’ve always seen us as a cult band to the extent that the way that the thing is constructed and the music isn’t always predictable or easy to digest. Also we were really strongly locked into the thing of this place that we lived in, Australia, this strange joint a long way from anywhere else and how it worked, what was going on in our minds about Australia. So to see that record actually break open for us, even if it was on a song that I wasn’t singing on, it helped the process. It added to the irony of it really. It just meant that we were aware that we were opening ourselves up to a larger audience. We went with it. It wasn’t like the idea of a bigger audience was strange to us. We thought fine, lets just keep pushing it and see what happens.

PC: The 10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1 album is now considered one of the most important examples of Australian Rock. How do you perceive it?

PG: Well firstly at the time, I didn’t know we were making something that was going to do as well as it did and secondly stand as well as it did. It felt good in the studio. We knew things were going the right way. But then you’ve got to move on. You can’t look over your shoulder all the time. It’s very flattering to have someone describe record like that. That’s terrific if that’s where it stands. But I think if we start to think of it in those terms, then we’ll never go off and make anything that’s decent, you know. So you’ve always got to be trying and I think Midnight Oil always does try. Both to move on from where it’s been, but also to improve where it’s been. But also, it just came at a good time in the band’s career. We were angry, we were young, we were hungry. But we were focused and I think that Rob Hirst’s writing in particular came to the fore. And Jim’s as well but the writing really started to come together. We also caught Nick Launay at a really good time in his career where he was really willing to go out on a ledge and see what he could do. A combination of those circumstances gave us that recording.

PC: Have The Oils been misunderstood over the years?

PG: Lyrics are very much what people make of them and different people are going to make different things of your lyrics. Someone can take a lyric and think that it’s all about the end of the world and someone else can take the same lyric and think it’s about the beginning of their love life. And I think that even though The Oils political and social content is something that has distinguished the band, at times it was really over emphasized when what we had done was marry words and music. Sometimes, I’ve had a sense of something but I haven’t been able to get it into words and the other guys have been able to put it into words really well. But it would mean nothing unless we had stuff that was working underneath it musically. And other times, we haven’t been looking for anything that is political or biting. At least three quarters of the current music makers that have access to the charts are fairly brain dead and conscious dead. And most of what they are on about is a convolution of emotional masturbation for a very small circle and a very small frame of reference. I think our frame of reference is basically just a lot broader than most peoples. Certainly most bands. And we are prepared to have a go at it even if it seems appearing very grandiose and profound and didactic and whatever. I think it’s just something that we’ve been prepared to have a go at. When you get it right and it coincides with what other people are feeling, then, yes, you do have a really strong record. But when you don’t, then everyone looks at you like you’ve come from another planet.

PC: At the peak of your success, did you start to feel like a rockstar?

PG: Bigness is not really the issue for us. I think the issue is if you are making the connections. We enjoyed to a limited extent being able to go out and play to the large numbers and find a bigger audience there. In some ways, that’s what people dream about. But I think at the same time, the artificiality of the lifestyle, not only the touring end of the lifestyle but also the business end of the lifestyle, where all the middle people between you and the audience in a country like America become expanded to an infinite number to what we as Australians have a limited capacity to deal with. We wanted to do it on our own terms and I think we did it on our own terms. That part of it for us was very successful and we count it as an achievement we can notch up the belt.

PC: Why do you keep touring after 20 years?

PG: I think that people overrate the difficulty of road life, because how lucky are you to go from city to city and have people cheer wildly when you go onto a stage. You walk off and someone hands you a guitar and asks you what you want to drink and generally treats you like you are someone special when you are not. That in itself is not so demanding. I think if it’s anything, it’s the total lack of reality that is damaging to people. Except when you have done it as long as we have, it has become our reality. It seems like a normal life to us. And it seems like a normal life to the people that we live with and out friends as well. So it’s not even an issue, except to the extent of not wanting to be away for too long. That’s obviously the big issue when you start to have kids and the tribe starts to grow under your feet, then you realize that you need to be around and be part of the tribe. That’s the only dilemma of it.

PC: A lot of people consider Peter Garrett to be Midnight Oil because you are the one with the high profile, but not only that, the other guys are very low key. But it’s really a very even workload within the band, isn’t it?

PG: It’s a group thing because it comes about as to the nature of the people playing the instruments. I think musically, I think Jim Moginie is almost the unsung hero in the band in the sense that he’s not chased around looking for the front page of guitar player magazine. He’s never sung his praises all that loudly. In many ways his focus has always been very much into what the music is doing and not so much what the business is doing and I think that’s whats kept us very healthy musically. So he has a lot to do with it, but I think Rob does as well because he’s a good writer and a prolific writer. And I think then the fact that we can actually construct stuff as a band and that nothing stays sacred in there. It’s all open for people to make contributions, so you are going to have contributions coming from Martin and Bones and you are going to have me coming at the last minute and saying “actually can we do this” and everyones like “oh really”. We have always leant to one another in order for Midnight Oil to really emerge.